Claude Monet. Grainstack (Sunset). 1891. Museum of Fine Arts, Boston

Read MoreThe Last Impressionist Exhibition: Cézanne, Seurat and Gauguin

By the early 1880s there was already a crisis in Impressionism. Although not formally affiliated with the Impressionists, Edouard Manet died of gangrene at a fairly young age early in 1883. The Last Impressionist Exhibition occurred in 1886. Monet and Renoir chose not to participate; their goals for art had changed and they did not feel connected to many of the painters who had more recently joined the Impressionist exhibitions. We will look at their mature work , and that of Degas, in our final session. At the 1886 exhibition the show stopper was Georges Seurat’s Sunday Afternoon on the Grande Jatte. Seurat and his circle developed a scientific method of applying color in dots, requiring the eye to blend. 1886 is also a period that sees the rise of Paul Cézanne, a painter who exhibited with the first Impressionist Exhibition, and by 1885 was increasingly focused on the structural brushstroke evident in his many versions of Mont Saint-Victoire (this link is to the Barnes version of 1892-1895). Finally, critics focused on the work of Paul Gauguin, whose paintings of Breton peasants and visions of a paradise in Tahiti would garner considerable attention in the 1890s.

Gender and Impressionism: Morisot, Cassatt

Several women exhibited with the Impressionists, the best known are the French gentlewoman, Berthe Morisot, and the American expatriate, Mary Cassatt. In paintings by Berthe Morisot, we experience Parisian life as an upper-class woman—the expectations for marriage, socialization within an apartment, and life as a working-class mother. While we may think that we the life of a woman was incredibly conscripted, Morisot also shows women both active outdoors and absorbed in intellectual pursuits. She also depicts her husband, Eugène Manet (Edouard Manet’s brother), directly engaged as a parent.

Berthe Morisot, Eugène Manet and his Daughter at Bougival, 1881. https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/archive/3/33/20160422163615%21Eugene_Manet_and_His_Daughter_at_Bougival_1881_Berthe_Morisot.jpg

Cassatt had not only the courage and the financial means to re-settle as an artist in Paris, she also enjoyed family support, especially of her mother. However, through her actions and her career, she challenged gender stereotypes. While friend Edgar Degas often had Cassatt pose as a model for his works, he depicted her posture and attributes in ways that challenged gender norms, depicting her in a public space, taking a more masculine stance or leaning on a man’s umbrella. These conventions likely cued viewers, accustomed to anti-suffrage caricature conventions, to Cassatt’s independence and non-conformity. Like Morisot, Cassatt not only depicts women who read, but also who drive or ride the omnibus through town. By the 1890s, she also becomes quite well-known for her depictions of women and children. Contemporary viewers must understand these works within the context of a push from several intersecting organizations to encourage women of all classes to become more involved in childcare and a movement to discourage the practice of hiring wet nurses.

Mary Cassatt, A Woman and a Girl Driving, 1881. https://philamuseum.org/collections/permanent/104447.html?mulR=1882744251|1

Impressionism and the Urban Scene: Caillebotte, Renoir and Degas

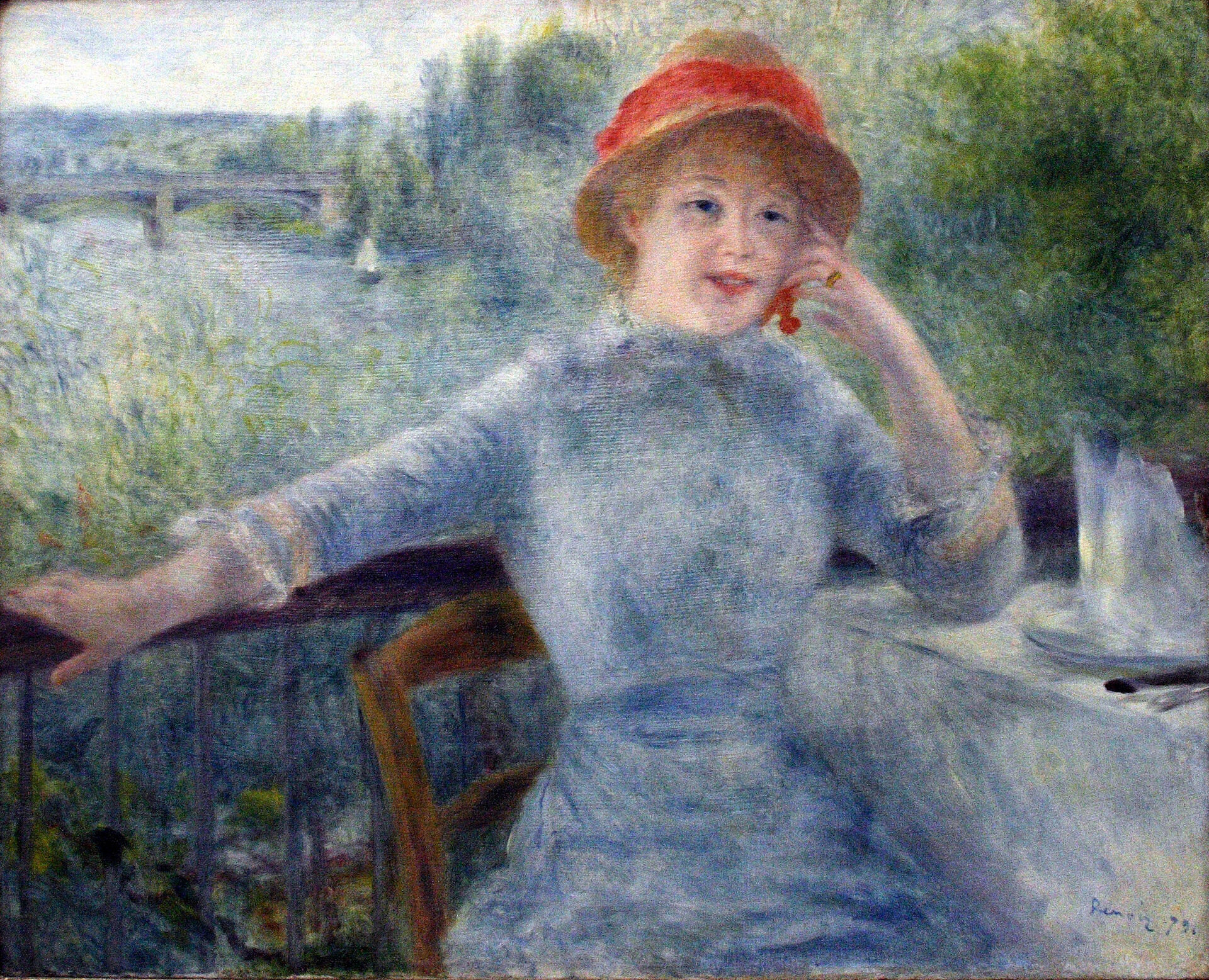

Paris was the center of the movement that came to be known as Impressionism and its many facets appeared on the canvases of the practitioners. Pierre-Auguste Renoir depicted many aspects of life on the fringes of Paris, the leisure and daily life of the working class, especially in his neighborhood of Montmartre. How and why did the public react so strongly to the images that we now see as somewhat light and sweet? We will consider the fashion and the color that is shown as well as other markers of modernity. In comparison, Edgar Degas sought out other venues of modernity. We will focus on images of dance and performance, in the cabaret and at the ballet of the Opera. Gustave Caillebotte depicts the architecture and the workmen of the Opera district of the city, the area around his apartment at Rue Halévy and on his strolls, at sites where population groups intersected such as the Pont Neuf. (Despite its name, this was the oldest standing bridge when he painted it!) Caillebotte also leads us to consider the rise of shopping as a element of modern life and as depicted in the canvases of the Impressionists.

: Halévy Street, View from the Sixth Floor (La Rue Halévy, Vue Du Sixième Étage) by Gustave Caillebotte, 1878

Painting the Suburbs en plein air: Bazille, Monet and Renoir

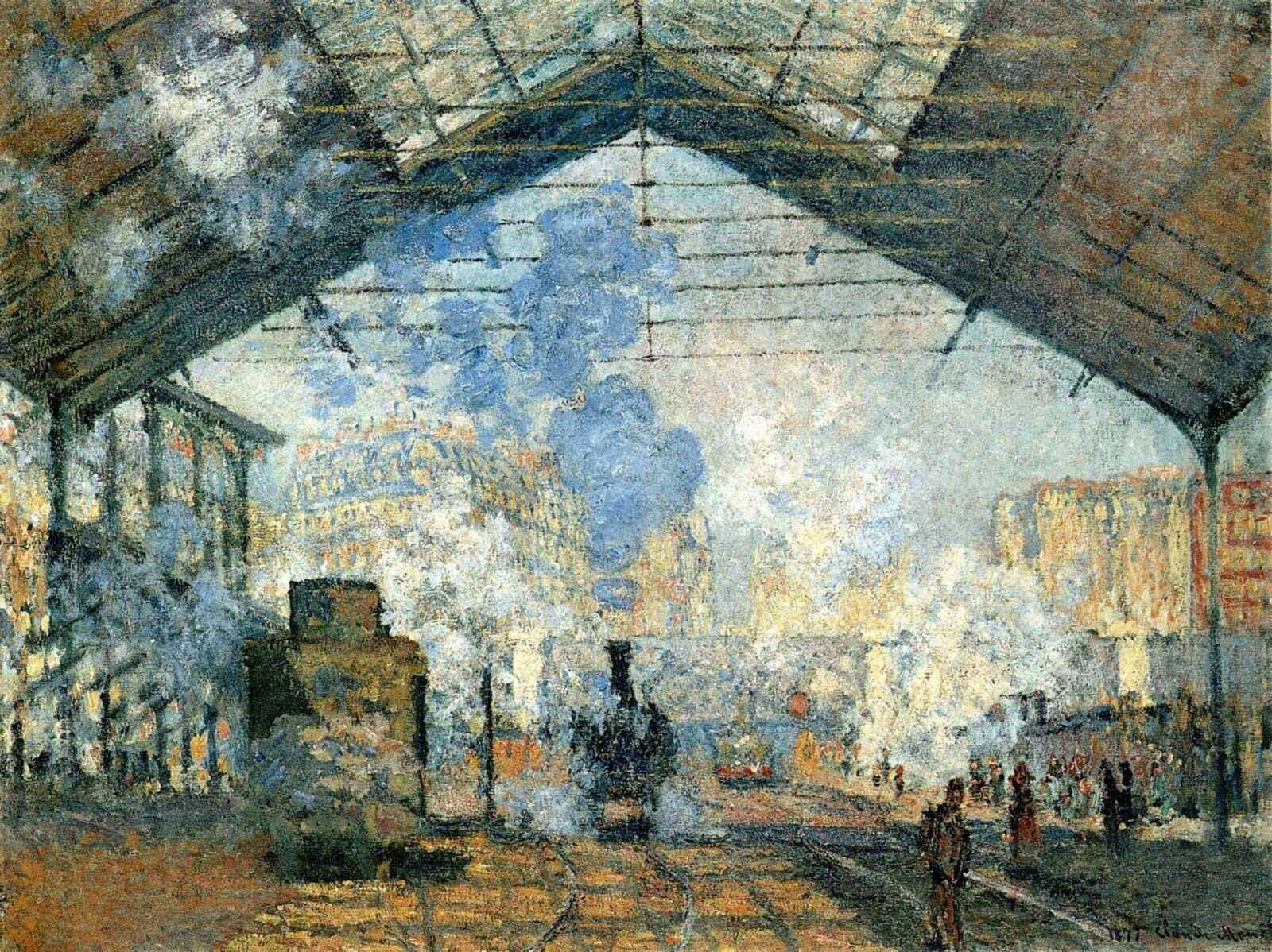

The artists who would become dubbed the Impressionists knew each other in the 1860s as young students. One of the most charismatic and innovative artists, Frederic Bazille (1841-1870) was a proponent of capturing the particular qualities of outdoor light and painting en plein air (outdoors). Unfortunately, he died in the Franco-Prussian war and never got to see his comrades band together as the Societé Anonyme, what we eventually have come to call the Impressionists. In this second session, we will focus primarily on this idea of painting en plein air as the Impressionists captured the new sights of leisure of the suburban countryside. They took the train from the Saint-Lazare train station out to towns along the Seine where they boated and ate at outdoor cafés. To explore this theme, we will take a close look at the early work of Claude Monet (1840-1926) and Pierre-Auguste Renoir (1841-1919). We will consider not only their biography, but also their particular brushstrokes, individual compositions and different palettes. Click on the image below to preview some of the images that we will look at more closely.

Welcome!

Impressionists were the radicals of the 1870s taking on modern Paris by storm. We will look at the origins of French Impressionism, the ways the group challenged accepted practice in form, subject and in the way that the market influenced their work. We will also consider how two such different artists as Edgar Degas and Claude Monet could be considered part of the same movement and look as well at the reasons why French Impressionism was one of the first avant-garde movements where women exhibited regularly with favorable critical notice.

Three Rebels: Courbet, Baudelaire and Manet

The Impressionists were radicals--not necessarily on the political left, but radicals in that they were trying to change the core of how art was made, exhibited and marketed. In this, and in their commitment to modern life, the Impressionists capitalized on the innovations and ideas of the painters Gustave Courbet and Édouard Manet and on the poet/critic Charles Baudelaire.

Gustave Courbet. Portrait of Charles Baudelaire, 1849. Fabre Museum.

Édouard Manet, Music in the Tuileries, 1862. National Gallery of London.